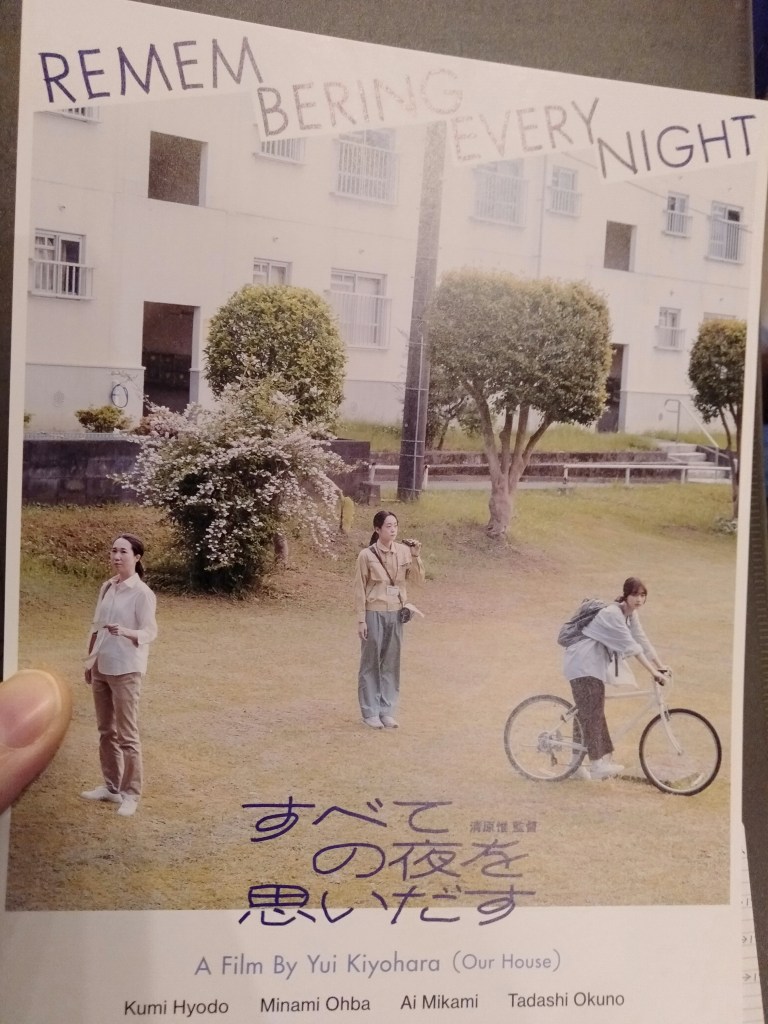

In 2017, director Kiyohara Yui released her first feature film, Our House (私たちの家), and established herself as a talent to watch. Though that film at times felt a bit like a workshop, it also revealed Kiyohara’s skill at creating an eerie, otherworldly atmosphere through careful framing, lighting, and sound design choices, as well as excellent casting. While she was beginning work on her second feature, originally meant to depict guests and staff on the last day at a hotel before it closes, the pandemic happened, and Kiyohara found herself spending a great deal of time in the Tama New Town community where she grew up. Though her film’s title, Remembering Every Night (全ての夜を思いだす), remained the same, the setting and the characters gradually shifted to Tama New Town and the depiction of a single day there.

It’s impossible to know what Kiyohara’s original idea for Remembering Every Night would have looked like, but I think the Tama New Town setting is crucial to this film’s power. On the one hand, this is a neighborhood like any other, full of long-term residents, most of them elderly. It’s a kind of self-contained community with its own parks, pathways, and recreation centers. On the other hand, it’s a remarkably specific kind of place—once an emblem of Japan’s economic prosperity and a sign of bright futures to come, these suburban housing projects are now falling into disrepair and are often home to older, single dwellers. As depicted by Kiyohara, though, Tama New Town is magical. It’s a place full of trees, grass, and gentle breezes (in a city that often feels like it doesn’t have any). It feels like a time capsule, calm and serene, shut off from the rest of the world. The people within it may often feel isolated, but they’re bound together, even if their connections can sometimes be difficult to see.

Remembering Every Night brings to mind other great works of naturalistic Japanese cinema like Cafe Lumiere (a Japan/Taiwan co-production), The Mourning Forest, and Maboroshi no hikari. Those are also films where it seems like nothing much happens, but what does happen is depicted with such an eye for detail that you can’t help but be mesmerized. Yes, Remembering Every Night is slow, and plenty of people will probably find it a little too slow, but Kiyohara is so skillful at what she does that I found myself completely swept away.

Kiyohara has made it clear that her primary concern as a filmmaker is the tenuous connections that bind people (or keep them apart), as well as the way that films can exist like symphonies, repeating certain images and sounds, bridging gaps between scenes with the faintest of hints that what comes after is related to what came before. With Our House, Kiyohara told a story of two different pairs of women living in the same house, seemingly in parallel universes and timelines, mostly unaware of each other but occasionally poking holes in the very thin wall between their two worlds. Remembering Every Night follows three women living or working in Tama New Town over the course of a single day: Chizu, a single, middle-aged woman trying to find a new job and reconnect with an old friend; Sanae, a thirty-something meter reader who ends up helping an elderly man who’s lost his way; and Natsu, a university student dancing in the park and mourning the loss of a childhood friend.

Just as the strange house was very much a central character in Our House, Tama New Town is a solid, beautiful presence in this film. The camera lingers on large trees blowing in the wind, long walks through the area’s many grassy knolls, and the view of a sunrise and a night sky seen through glass bowls in an apartment window. A lengthy opening shot slowly tracks left to right, then up and down over a group of musicians rehearsing in the park, then off to the side to reveal someone lying on a bench and flexing their hands in the air. It gives us the feeling that we’re sitting in the park with them, our gaze slowly taking everything in.

Chizu, Sanae, and Natsu have brief, indirect encounters with one another. Sanae, making her rounds to read meters, sees Chizu perched in a tree after trying to rescue a child’s shuttlecock. Chizu notices Natsu dancing in the park and briefly copies her moves—she thinks that Natsu hasn’t noticed her, but she has. Later, in a beautifully filmed nighttime scene, Chizu watches Natsu and her friend set off fireworks, the light of sparklers reflecting on her face in the darkness.

There are also interesting questions raised about records, remembering, and impermanence. Chizu goes searching for an old friend armed only with a postcard she received several years before saying that the friend had moved nearby. As she searches, a woman she encounters asks if she has the person’s Line contact info, and we guess that Chizu probably doesn’t. Natsu goes to a photo developer (yes, these still exist in Tokyo) to try to pick up photos that her deceased friend had taken a long time before. Natsu and her friend visit a museum of Jomon period artifacts and marvel at a time when written records didn’t exist. The elderly man that Sanae encounters, meanwhile, seems to be living out his life of forty or fifty years before, when Tama New Town was thriving. The past weaves into the present, and frequent shots of the obviously decaying sidewalks and buildings in the neighborhood remind us that the future is uncertain.

There’s a sadness to Remembering Every Night, but it’s not nihilistic or grim. The sadness is mixed with the beauty that comes from knowing that so much of what we value in life—visits with friends, a bike ride on a mild summer day, fresh-baked sweets, fireworks displays, the very home we live in—is ephemeral. Tama New Town, we sense, will not last much longer—as its residents continue to age and pass away, it will probably fall further into disrepair. Kiyohara depicts both the beauty of the now and the sadness of that decay in a delightfully subtle way, leaving us with the satisfying feeling of having spent time in a very specific world with very specific people, following the tangled threads that bind or cut them off from each other.