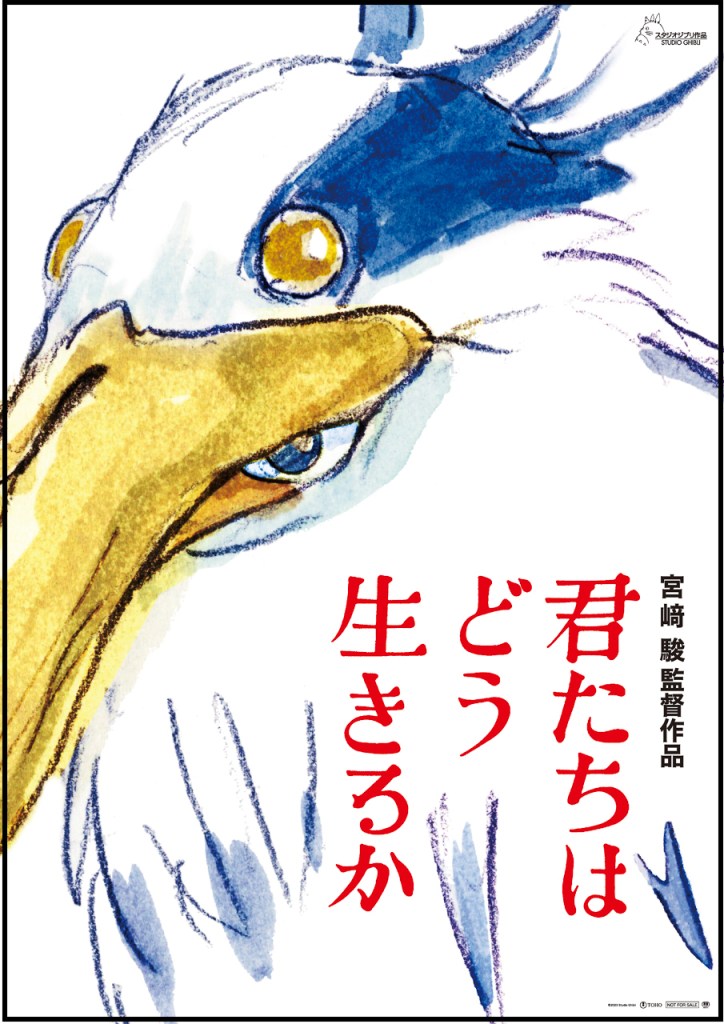

Hayao Miyazaki and his team are undoubtedly masters of their craft. It’s been ten years since Miyazaki directed a film (the wonderful, if divisive, The Wind Rises). This time around, Studio Ghibli made the shocking decision not to do any marketing for Kimitachi wa dou ikiru ka, which is being released in English as The Boy and the Heron. No commercials, no promotional events, no merch—just a single, decidedly odd-looking poster. A Miyazaki film is enough of an event that the studio probably felt that “no marketing” was a legitimate marketing strategy.

And it seems they were right—theaters have been packed since the film opened. My own screening at 9:50 a.m. on a weekday was almost completely full.

The first twenty-five minutes of The Boy and the Heron induce the kind of state that I long for from movies—a feeling that comes from just surrendering to an experience, of letting the images and sound wash over you gently, happy to be in this world that a master filmmaker has created for you. Miyazaki knows how to take his time, and we can take our time as well, soaking in the images of rural Japan, the delightfully specific sound of feet on the wooden boards of a traditional Japanese home, the complicated family relationships and characters with enigmatic motivations.

And then unfortunately it all goes off the rails.

Going off the rails isn’t always a problem, especially for Miyazaki. One of the joys of his movies is that many of them feel unsafe. He may be most fondly remembered for sweet and and nostalgic coming-of-age stories like My Neighbor Tottoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service, but he’s never been afraid of gore, goo, and trippy weirdness. From the blood and vomit in Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away to the huge insects and murderous giants in Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind, Miyazaki’s films have always had a dark and sometimes hallucinatory edge to them. And it works, because even when the edges get unstable, the center usually holds.

But this time the center doesn’t really hold. Instead, we get a parade of familiar Miyazaki imagery and story beats—odd-looking monsters, little old ladies with bulbous noses, shapeshifters, a young protagonist forced to take on more than they can handle, a mysterious and dangerous alternate universe, and an idyllic rural setting. But everything feels muddled. I expect Miyazaki’s films to inspire awe and a sense of unease or discomfort, but I don’t expect to feel so disconnected from everything. I was never able to get a real sense of what this alternate world was about, or feel any sort of connection to the people and creatures who existed within it.

The film begins during World War II, with young Mahito moving from Tokyo to the countryside after the death of his mother. Mahito’s father manages factories that make war munitions (something true of Miyazaki’s own father), and the father in the film has relocated to the countryside to marry his late wife’s younger sister, who is pregnant. Mahito is still deeply traumatized by his mother’s death and struggles to adjust to life in the countryside, living alongside a bevy of sweet little grannies, his mysterious new mother, hostile local boys, and the overgrown and crumbling tower near his house.

This on its own would have been more than enough for a solid and engaging film, one that might have explored the same complicated issues explored in The Wind Rises (Mahito’s father seems blissfully unbothered by the kind of work he’s doing, though his wife, and Miyazaki himself, clearly seem to be haunted by it). While Mahito and his family live peacefully in the countryside, Tokyo is being firebombed, and his father’s factory is making the plane parts that will send thousands of people to their deaths. And what of the relationship between Mahito and his new mother? It’s subtle—Mahito is perfunctory, but not hateful, while Natsuko’s intense cheerfulness is clearly covering for something.

But then a talking heron shows up who pulls Mahito and one of the unsuspecting grannies into an alternate world, and all of those potential threads are abandoned. It’s at this point that the plot becomes so convoluted that there’s almost no point describing it, though it involves time travel, murderous giant parakeets, little white blobby things (this film’s version of the coal sprites from Spirited Away or the kodama from Princess Mononoke), a wizard, and Mahito’s quest to save his new mother. After watching the film I honestly wondered if my non-native-level Japanese ability was one of the causes of my confusion, but apparently not—the very detailed Wikipedia summary of the film revealed that its major plot points were just as I’d perceived them in the theater. They just didn’t make any more sense to me on the page than they did on the screen.

The Boy and the Heron will surely have its fans. But for me it was just…overstuffed. Its fantastical world and characters do not follow any sort of internal logic, meaning that the consequences of characters’ actions don’t carry any real weight. It’s hard to care about the result of Mahito’s quest when we’re not even sure that any of what is happening to him is real, or what his victory would even look like. In contrast, we care deeply about Chihiro, San, Ashitaka, Nausicaa, and Sheeta, because even though the worlds they inhabit are weird, they have their own rules and logic, and the protagonists emerge victorious by following those rules and becoming more confident, adult versions of themselves. Mahito, on the other hand, talks to birds, sails a boat, meets a girl, guts a fish…and none of it really seems to matter.

To be clear, there were moments in this film that dazzled me, even after it abandoned its more straightforward storytelling style. Miyazaki is still a master of combining music, sound, and images to create things that I’ve never seen before on screen. But The Boy and the Heron feels like a movie Miyazaki made purely for himself, recycling his favorite characters and images in a way that brings him pleasure but doesn’t really add up to a meaningful film experience.

If this is indeed Miyazaki’s last film (as he has claimed), I’m sure more than a few people will be dazzled by it. This time, though, I wasn’t one of them.